- Discounts

- Return policy ?

-

English

English

Product added (x)

Cart (0 products) Cart (1 product)

Wushu Weapon manual by Oscar Reyes

ForewordWushu (Pinyin: wu3 shu4; Chinese martial arts) adepts are always in search of an ideally inexpensive, source of the great diversity whushu weapons.

Low-price brackets naturally impose limitations on quality. The construction of a "ready-to-use" weapon, though easy, is work-intensive, which greatly raises the price tag, though not necessarily the quality of the weapon parts. The Chinese have solved this dilemma in an original way:

Low-priced Chinese wushu weapons are almost always delivered as packages containing just that minimal number of parts that require very specialized labor. Such a package contains a blade made from mass produced blanks, partially finished by an artisan blacksmith. The wooden parts, lathed or machine-carved by the hundreds, are summarily adjusted to the blade with partially finished mass-produced fittings, and made by casting or semi-artisan procedures.

In these parts, provisionally assembled to prefigure the finished weapon, there is no pretense of a complete product; indeed all precautions in the quality of the adhesives involved, and even in the weapon design have been taken in order to make this assembly provisory; the product is clearly intended for one or more additional steps requiring low skills, in an hypothetical production line.

Such a weapon package, as delivered, is usually worthless for training, though has the potential to be converted into an excellent practice weapon. In this regard, it appears to represents the Chinese conception of a weapon in kit form, and so it will be called hereafter.

For the Chinese wushu adept such form of weapon presentation provide, in addition to the ancient tradition in which they grew, all the instructions they need to re-assemble these parts into a good and serviceable weapon. All the extra parts eventually needed to finish the assembly of these Chinese weapon kits are assumed to be locally available –in China.

There is no Western equivalent of a Chinese wushu weapon kit. Wushu weapons made in Western countries are assembled from parts made by industrial techniques more elaborated than those used for Chinese weapons; thus these parts are better finished. Also the weapon designs are modified as to eliminate all need of conditioning to produce a serviceable exercise weapon; Western made wushu weapons are ready for practice as bought.

One disadvantage of the "ready to use" approach is a sacrifice in the diversity of weapons available, which is much reduced in the Western facture. Other sacrificed feature is the price, which is at least doubled comparatively to that of Chinese-made weapons kits including parts of equivalent or even better quality. Finally, the most important sacrifice is the disappearance of that appealing artisan aspect of the Chinese wushu weapon facture, which is absent from the Western production.

In this regard, always the blades of even quite cheap Chinese weapons are decorated with incised calligraphy and drawings; often these are even inlaid in copper and brass. The patterns for these drawings are transferred to a batch of blades, and then manually incised on each one. This is true for other decorations sometimes incised in the scabbards and handles. It result that is impossible to find two identical weapons in a batch dryly described by the supplier as by catalog designation, as if it were a standard mass produced object.

Considering the fast rate of China's industrialization, we may belong to the last generation that has access to such kind of affordable Chinese semi-artisan crafts. Exercise wushu weapons define on themselves a class objects whose interest, as decorative items, goes beyond their original utilitarian purpose. In this regard, many affordable wushu weapons of interesting facture, whose continued availability I took unfortunately for granted in the middle 1980's, now are almost impossible to find. Kits for rare exercise wushu weapons also are good investments for the weapon collectors.

However, this semi-artisan nature of the parts of Chinese wushu weapon kits often disconcerts the average Western buyer, who is accustomed to a better finishing. Also the Western wushu adept would appreciate a kit where other parts needed to complete the weapon are included, as pre-cut weights made of high-density metal to assist in the weapon balance, and materials difficult to find locally, as lengths of cord or leather strap adequate to wrap the handle, finishing products, traditional weapon decorative items, etc.

Above all, a wushu weapon in kit should provide that most essential component in a kit: a carefully written complete Instruction Manual intended to guide the buyer through the steps to complete her -or his- weapon.

A misunderstanding of the Chinese kit concept bears a large share of the responsibility in the Western misconceptions of wushu weapons. The most likely outcome of these frustrating, but charming and potentially excellent weapons in Western countries is a humiliating life as a misbalanced rattling weapon, often cobbled together with bits of twine and electrician's tape. Such weapons are seen even in hands of highly competent Western wushu adepts.

My intention here is to provide the serious Western wushu adept with a first draft of that so long needed "Practical Manual for the Assembly and Conditioning of wushu Weapons".

The most usual choices as first wushu weapons learned are double-edged straight swords and sabres; hence is for these that this first installment of the "Manual" is principally devoted. On a near future it will be extended to cover others examples of the rich fauna of wushu weapons.

I practice T'ai chi intensively since nearly 22 years; I become amateur repairman and restorer of exercise wushu weapons first by need, later by pleasure. The examples in this Manual are mostly illustrated with the rich diversity of weapons found in the ChinaTown-Shop (CTS) catalog; however the solutions proposed in the Manual are susceptible of being applied to similar generic exercise wushu weapons that can -at least in principle- be obtained elsewhere.

I'm connected to the CTS staff only as benevolent contributor. I took a personal interest in the CTS venture as being a valuable educational tool, which may at last shake off some received ideas from the Western wushu community.

CTS achieves this goal just by offering the richest and most affordable source of wushu weapons in today's WEB. A supplier worthy of continued attention. CBS staff realizes innovations may change forever the marketing of wushu weapons. For example, CTS offers a limited possibility of realizing affordable customized combinations of parts taken from diverse weapons from their catalog. I hope this interesting idea will further develop, and that will continue to be other hallmark of ChinaTown-Shop.

Other unique feature of CTS is that its staff's acknowledges the gap existing between the Chinese wushu weapon products, and the expectative of the Western wushu adepts. Thus CTS staff currently considers to further enrich their catalogue with accessories that facilitate wushu weapon conditioning, but are of difficult access in Western countries (for example, lengths of specialized woven cord or leather strap to wrap weapon handles, stone rings, to assist in ballasting sword tassels, etc.; these points will be further examined in this Manual. In this regard, feedback on these pages would be welcome, both by the ChinaTown-Shop staff and me.

My qualifications as first contributor and self-appointed editor of this Manual are:

First, a formation in Biology, Chemistry and Physics, which gives me a good understanding of the materials I use, and some experience in delicate manual work.

Second, more than 22 years of theoretical and practical study of T'ai chi.

Third, I'm an avid builder of high-end kits of historic Western keyboard instruments, which as a class present many similarities to the Chinese weapon kit concept.

Fourth, and most importantly, I'm blessed with a select group of Chinese and Sino file friends always willing to lend me their knowledge of Chinese traditional arts.

However, the historical and technical points of view raised here are exclusively my own responsibility. Please do blame for them neither the ChinaTown-Shop staff, or my friends.

From the point of view of a wushu weapon repairman doubled of a aging swashbuckler, often the experience acquired in the shop seems to contest some sources and commonplace notions about wushu weapons. This is not surprising, since most of the available information on extant historic weapons is of little relevance to wushu practice.

The description of the ideal weapon that our assembled kit emulates must be inferred from fragmentary evidence that includes actual shop experience, historical sources that often do not raise over the anecdotic level, and actual performance with arguable reconstructions of historic weapon. The approach just described has proven its value in other fields [Reference 6].

Lost in this maze, the wushu weapon repairman and performer must steer its own way. In these cases, since I must produce at a workable weapon as end result, I apply the principle that "a decision perhaps wrong is better than no decision at all".

If you don't agree with these 'techno-historic' considerations, or have better technical solutions than mine, by all means write to me, and correct my mistakes. If the situation requires so, I'll apologize in these pages, and present your solutions here under your byline.

Given to my limited time availability, I CANNOT keep these pages as one more weapon forum. However, if you have specific questions relative to your own weapon project, I'll put them in my "urgent" mail list, and I answer them as soon as I can.

Shop, Tools, materials and measures

What I pompously call "my shop" lives in five boxes stored in a small cupboard (64 x 31 x 70 [cm]). I use as a workbench a sturdy restored cable spool of 65 cm diameter lying on a side, which doubles as coffee table. The spool's central perforation is useful to keep vertical the weapon under work. I own an articulated lamp equipped with a large reading glass, a luxurious item that can be substituted by a hand-held reading glass and a good spotlight. In fact, except for small tools as the couple dozens metal files of different shapes, and a small hand-held powered drill with flexible transmission, my "shop" is simpler than that of the average French citizen.

The tools needed even in a major project are simple and inexpensive. Given the small sizes of the parts to be shaped, the tools used do not need to be of prime quality. Buy your tools as you need -and found- them. If some sculpting is needed, a common cutter with an adjustable blade that can be secured in place, and a provision of blades, might be all you will need.

Small pincers and clippers for electric work will be useful for building ballasts from lead/tin soldier adjuvant in wire form, as will be described in the corresponding section.

An indispensable special tool is a fine-toothed rib saw; the best, equipped with a cutting box, are made for hobbyists. An assortment of cheap metal files of different sections (round, flat, triangular), and an assortment of wet abrasive paper (between 360 - 1200 grit) will cover most of your needs for sanding weapon wood parts, and shaping and polishing metal surfaces, and sharpening your tools. Cheap oil stones with a coarse grit and a medium-coarse grit surface can be found in stores specialized in Chinese cooking utensils. These are destined to perform coarse shape adjustments in weapon parts before giving a finish with wet abrasive paper.

An excellent all purpose and inexpensive tool for eliminating paint, etc, and finishing slightly rounded or flat small wood surfaces (for example scabbards) is the scrapper, a rectangular plate of cutting steel that is kept sharp by grinding an edge perpendicular to the plate on a piece of wet fine (grit 600-1200) abrasive paper held on a flat hard surface, for example a sheet of glass.

Beside their intended use, a set of wood flat and rounded chisels will also be useful to cut off and shape ballast from sheets or bars of lead or lead/tin alloy.

A useful precaution to reduce the risk of hurting yourself when sculpting wood is to use very sharp tools, cut away from the body, and hold the work on a vice or against a support. Over all never work when your hands give signs of fatigue. Always proceed by removing wood shavings as thin as possible; if you cannot do this, the tool you're using needs either re-sharpening, or a fresh blade.

Some projects are made easier by using a powered drill. A flexible transmission and bit holder may be useful for holding and using specialized bits.

Glues are a very important part of weapon conditioning. Ancient swords parts not riveted or penned were adhered with hide glue, an excellent adhesive for surfaces involving heterogeneous materials; unfortunately hide glue requires a highly skilled workmanship to produce good results. The best substitute of hide glue is epoxy glue.

Quick setting epoxy glue is to be reserved for joints that are under low strain, and that are not exposed to the air; this glue produce reversible joints, cleavable along the joint line by a brisk rap. Any other kind of quick setting glue is adequate for joints exposed to the air; gel neoprene glue is a good choice in this case.

Slow setting epoxy glue produces highly resistant joints; also is ideal to fill interstices and cavities that are not exposed to the air. The long time available before hardening start (about 5-8 hours) allow this glue, with the consistence of honey, to flow by gravity and infiltrate between parts inaccessible to the worker.

Epoxy glues are expensive, and wood surfaces should be glued with plastic carpenter's glue. The best kind, called "orange glue" in America, is found only in specialized hardware stores. It has a creamy orange color, and its resistance to strain is only comparable to that of hide glue, or of slow setting epoxy glues. Orange glue is available in France only to professional cabinetmakers, which may accept to sell you small quantities; I do not know if orange glue can be obtained elsewhere in Europe. Joints obtained with slow-setting plastic white carpenter's glue (available everywhere) support much less strain than those made with orange glue. If orange glue is not available, wood joints that support strain should be glued with slow setting epoxy glue.

Two indispensable measuring tools are a cheap plastic vernier caliper, and a flexible measuring tape of two meters, in steel or fabric. A common kitchen scale is a welcome tool in wushu weapon conditioning.

Along these pages I'll use the Metric System for measurements:

1 meter (m) = 100 centimeters (cm) = 1,000 millimeters (mm)

1 inch = 25.4 mm

1 kilogram = 1,000 grams = 1, 000 cm3 of water

1 pound Av = 454 gr

You should keep a detailed journal of your projects, including pictures taken at critical steps of your work, weight and measures of components, materials used, etc. Include on it every piece of wushu folklore related to your project.

Decoding the Chinese exercise straight double-edged swords.

T'ai chi swords

For the knowledgeable wushu adept, stating "the ancient Chinese weapons were very subtle" seems a pleonasm. However a great majority of these dismiss the exercise wushu weapons as mere choreographic props, a visual aid uniquely destined to "help to learn the gesture" during the study of a weapon form.

The search of a choreographic prop has motivated the creation of one of the most common practice wushu swords, the "T'ai chi sword", a collective designation that includes swords of diverse shapes and forms, currently of weights in the 300-600 gr range. Despite its name, the T'ai chi sword usually does not correspond to a sword created purely for T'ai chi practice. This class, including also excessively light and flexible wushu weapons, do not represent any historically real weapon, and was uniquely intended to fill, in addition to their choreographic role, other needs of the modern general wushu adept that are unrelated with the theory of the weapon.

For example, in the China's Post-Republican period, public practice with realistic weapons was restricted; unfortunately this is also often the case today in some Western countries. The posession and public utilization of light and ultra-light flexible weapons was better tolerated; also they are inexpensive, and easier to transport. Given their low blade weight, comparatively to that of their hilts, "T'ai chi" swords require little or no ballast addition, and their conditioning for wushu practice is essentially limited to the consolidation of the weapon.

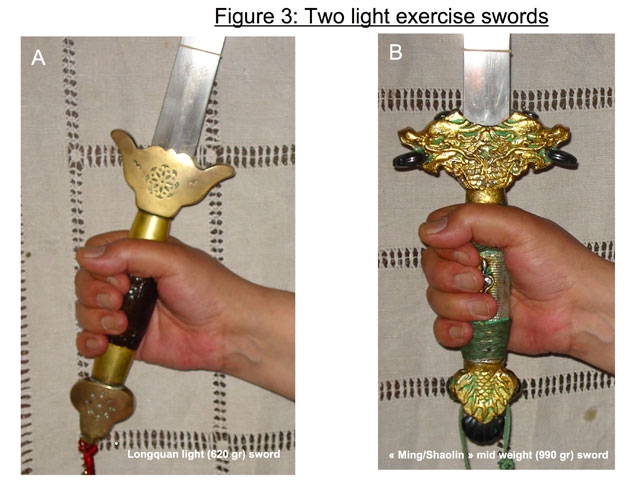

In this regard, the sword of old Lungquan facture shown in Figure 3A

is an example -albeit of better quality than the average- of this "utilitarian" exercise wushu sword concept. Its blade is fully flexible - soft rather than springy, thus easily deformable. Despite its relatively high thickness, its flexibility matches that of much thinner blades, which are dangerously sharp by reason of their very thinness. In this regard, this sword fills well the needs for a portable, very handsome, and fully harmless "weapon".

T'ai chi swords as this have identified themselves, for the wrong reasons, with many fantasies and misconceptions of some misinformed Western –and Chinese- wushu adepts. However, T'ai chi swords represent only a fraction of the types of exercise wushu sword exported by China; the CTS catalog gives a much more realistic example -albeit still incomplete- of the great variety of wushu swords.

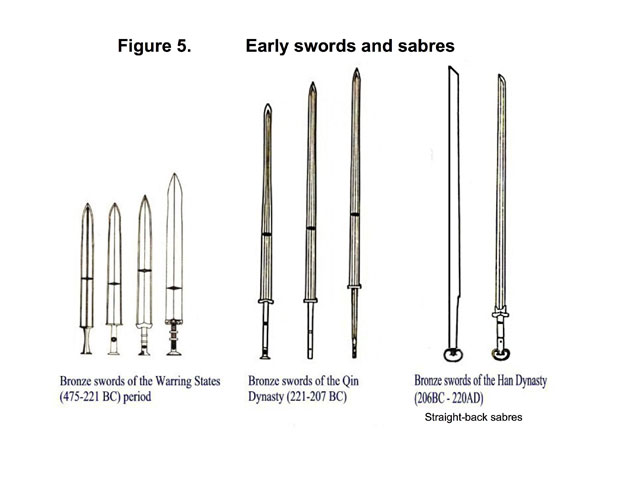

The tradition of the Chinese double-edged straight sword or (Pinyin: ba3o-jia4n, or simply jia4n; hereafter sword) is nearly 2,500 years old; the oldest swords appear in the Spring and Autumn Period (722 B.C.-481 B.C.). These were broad bladed, made of bronze, measured 60 to 70 cm, and weighed between 600 to 1000 gr. Such swords survived up to the Warring States Era (475 B.C-403 B.C.)

The long swords (87 cm-110 cm) appear during the late Warring States period and become the dominant type during the Qin (221 BC-206 BC) and Han (206 BC-220 AD) dynasties. Undoubtedly the possibilities of these new swords stimulated further developments of the Chinese fencing art.

Poetry from these periods already describes 'sword dancing' forms, which might represent the equivalent of today's sword forms. Short sword forms attributed to the Spring and Autumn period [Reference 1] show few essential differences with the forms for the long sword compiled later within the Shaolin, Wudang and T'ai chi wushu systems.

Some time later these fencing forms split in two major wushu systems described in 1669 by Huang Zonyi, an scholar from the Ming and Qing era, who defined the characteristics of a Northern 'External' wushu or Shaolin school, and of a Southern 'Internal' wushu or Wudang school.

The Shaolin school, named for a Henan's Buddhist monastery established in 497 AD, systematized the methods of many wushu schools; its name has become generic to designate other Northern wushu forms not included in the Shaolin system. As a rule, Northern wushu styles, including Shaolin favor semi-rigid light swords, probably close to 900 gr in weight [Reference 2]. A careful inspection of the surviving Shaolin sword forms does not show essential differences with the surviving forms of internal sword as T'ai chi and Wudang.

The internal or 'Southern' wushu school's birth is historically obscure, and appeals to a mythical figure named Zhang Sanfeng, most likely a composite of wise men who would have lived between the Tang and Yuan dynasties (the "accepted" birth dates of 'Zhang Sanfeng' are 960, 1247, and 1279). The Zhang Sanfeng teaching somehow passed to the Wudang Taoist monasteries, and to the T'ai chi creators

The historical trace of T'ai chi reappears at the 16th century, when Chen Pu (first generation of the Chen clan), established in what today is known as Chenjiagou or Chen Family Village, in Henan. Chen Wangting (9th generation, 1600-1680) realized the first formal codification of the Chen family martial art practice that gave issue to all present day T'ai chi forms.

The basic similarities of the surviving sword forms of the internal and external wushu schools, otherwise different in philosophical principles, are evident. Indeed, all these schools claim as the common ancestor of their sword tradition the already elaborated ancestral sword forms that date at least from the Spring and Autumn period, which after adapting to the new heavy Qin swords, were transmitted essentially intact until today.

Searching for a wushu weapon "kit", or how to read a dealer's catalog

The generic heavy sword

Defining a more genuine exercise wushu sword

The best criteria to define a sword adequate for genuine wushu training is to describe the military specifications of the weapon for which the sword form was created.

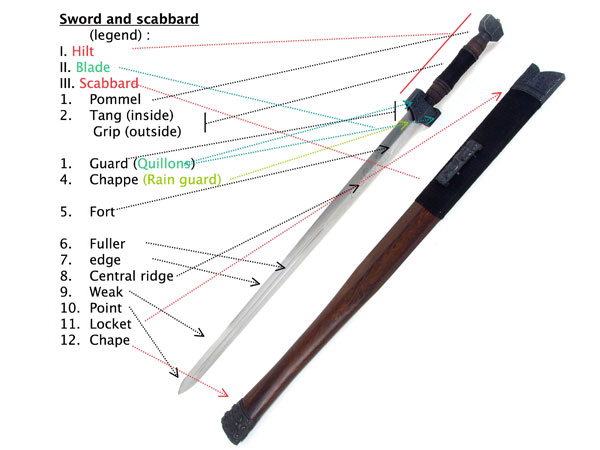

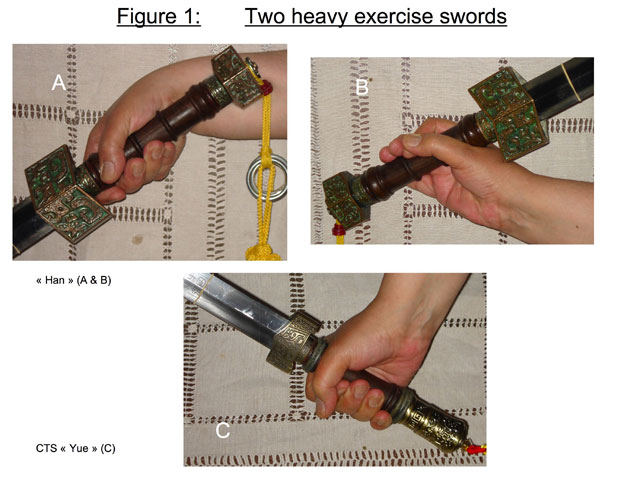

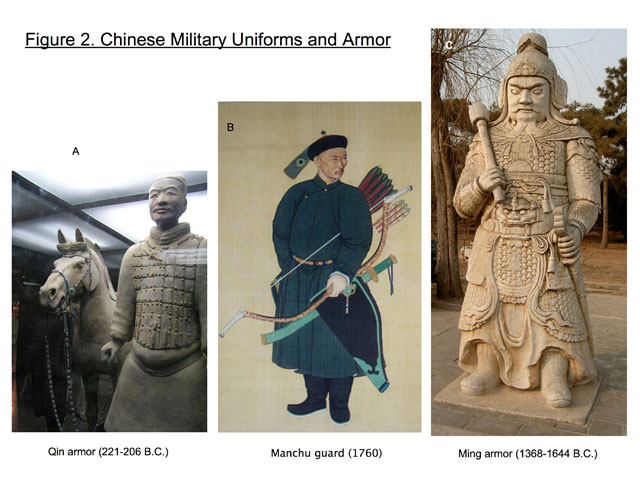

This task requires for some guess work. If we accept that the sword forms surviving today are indeed representative of those existing 2500 years ago, the sword indicated for practice should show features of the long and heavy weapons of the late Warring States and Qin periods. These swords (Figures 1 & 5; Tables 1[a, b, c]) must have had the potential to penetrate the bronze scale armor of the period (Figures 2A & 2C). Even in the case of advanced steel swords, is unlikely that blades with a thickness of less than 4-5 mm could be up to that role.

The lighter swords favored by the Shaolin system (Figure 3) probably belong to a military tradition were the scale armor was not used (Figure 2B). Even in such a case, we must assume that the blade rigidity of such a sword was sufficient to pierce a light padded coat of leather or cloth. This task still requires a fairly stiff blade. Such sword blades can be bended -admittedly with some effort- to about 30 degrees off the weapon axis without breaking or loosing their shape [Reference 2]. I have conditioned a few swords equipped with fairly good blades having these characteristics; these weapons usually fall in the weight range of 900- 1000 gr, including small tassels.

Introduction to the concept of a "well balanced sword"

A common feature for all swords: the distance Grip - Center of Gravity.

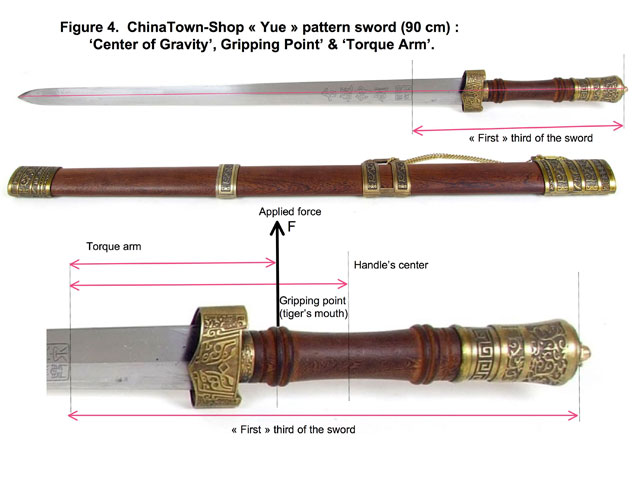

The most important factor that determines the handling characteristics of a sword is the distance between the equilibrium point and the "gripping point" at the hilt (Figure 1A, 1B, 3A, 3B, and 4). In the Figures 1A, 1B, and 3A, 3B, the Center of Gravity is indicated by a rubber band.

A "well balanced" sword is a rather obscure concept even for the expert adept of the wushu sword. I know of at least different two definitions of this concept; I will present these in the order of my personal preferences.

Above all, a well-balanced sword is one that handles well, that is, one that adopts easily the attitudes required by the sword form performance. The above definition, which makes easier to describe the features that make a sword to be well balanced, present two variants: one for basic learning and other for advanced practice.

Physical parameters of a well-balanced sword

Center of gravity

The handling of a sword depends mainly on the interplay of at least three factors.

One of these is the "center of gravity", a concept borrowed from physics. For a sword, the center of gravity is essentially the place were a sword can rest when is in perfect balance -or equilibrium. In a sword suited for wushu practice usually the center of gravity is located near the first (or hilt's side) third of the weapon. Frequently an equilibrium -or balancing- point thus located is taken as the hallmark of a well-balanced sword, but this is only part of the story (Figure 4).

Gripping Point

The weapon gripping point is determined by the hilt's place where the thumb and index can get a sword's grasp closest to the hilt neck and handle during the most extreme weapon movements, and yet avoid the interference of the guard with the wrist and backhand.

The circle formed by the thumb and index in grasping position is designed in Chinese as "Tiger's eye" (Pinyin: hu3 ko3u), and is considered a critical reference point to encode the positions of the sword's hand in the diverse sword forms. Though all the hand grasps the sword, usually the index and thumb held most of its weight, and serve as the point around which the weapon pivots. The Tiger's eye has also a major part in communicating the body strength to the sword.

The quickness of the sword's response to a determined amount of force will depend of two other parameters: the distance between the gripping point (Figures 1 & 3), and the center of gravity, and the sword's angular momentum.

"Torque arm" and "angular momentum" of a sword

The handling characteristics of a sword are related to the time that the sword takes to turn around its center of gravity under the effect of a force F. For simplicity this force F is assumed to be perpendicular to the sword, and to be applied at the "gripping point".

The distance between the gripping point and the center of gravity is the sword's "torque arm". The product between the torque arm and the force F determines a rotator force named Torque that reorients the weapon around itself.

The "angular momentum" of a sword, is a physical concept related to the mass distribution along the weapon. A sword with a high angular momentum will opposes to sudden changes in orientation. For a same Torque, and sword weight, a weapon with a low angular momentum will react faster than one with a high angular momentum. As a rule, for swords of the same weight and length the angular momentum increases as the ratios 'root/tip' decreases (Table 2).

Before being balanced, most heavy sword kits have the center of gravity located near the middle of the assembled weapon; the task of conditioning the weapon for exercise reduces to shift the center of gravity closer to the part of the sword intended as grip, or gripping point, until a convenient Torque arm is achieved. Most sword adepts admit that a Torque arm of 11-13 cm is convenient for basic training and exhibition purposes; such a Torque arm coincides with a displacement of the center of gravity to nearly the "first" (next to the hilt) third of the sword length.

This is done by adding ballast to the hilt. The ballast needed for placing the center of gravity nearly the first third of the sword length is roughly evenly split (Table 1a) between ballast permanently included in the hilt, and removable ballast included in the tassel.

Table 1a. Distance Center of Gravity- Gripping Point" ("Sword's Torque arm")

| Sword Type | Length | Weight complete with tassel | Center of gravity with tassel (%) length | Torque arm Center of gravity - gripping point | Distance center of gravity - handle's midpoint |

| Light "Lingual" (1) | 104 cm | 620 g | 28.8 % (1/3.5) | 13 cm | 19 cm |

| Light "Ming/Shaolin" (2) | 98 cm | 990 g | 28.7 % (1/3.5) | 11 cm | 17.5 cm |

| Heavy "Han" | 101cm | 1887 g | 30.0 % (<1/3) | 12 cm | 17 cm |

| Heavy CTS "Yue" | 92cm | 1248 g | 32.6% (<1/3) | 13 cm | 18 cm |

Notes:

(1) A restored quasi-artisan sword belonging to a style frequent in the Longquan [Ref 3] production around 1980. The weapon is only consolidated, and conserving the original kit equilibrium point; it has a very flexible blade. Swords of these characteristics have disappeared from the exercise wushu weapon market.

(2) Sword hybrid composed from two different kits; the blade characteristics are close to the optimum desirable for the practice of Shaolin sword forms ([Ref 2, and see Figure 1 B)

Table 1a. (legend). Distance Center of Gravity- Gripping Point" ("Sword's Torque arm") in some light and heavy finished wushu swords.

The measures of in the Table 1a establish the gripping point assuming a symmetrical griping position with the palm rolled around the middle of the handle.

*******

The purpose of Table 1a is to underline the similarities in the parameter "Sword's Torque arm" for finished wushu weapons of very different weights, lengths, and geometries. The differences between these weapons are underlined in Tables 1b and 1c. Thus the torque arm appears as the fundamental parameter in the description of the handling characteristics of both light and heavy Chinese swords.

In a weapon thus "well balanced", the removal the tassel will displace the weapon center of gravity appreciably forward the first third of the sword length (about 4 cm for heavy swords; see Table 2), making it distinctly tip-heavy; despite this, such sword will also have a longer torque arm, and under usual application of strength at the gripping point, it will react faster than the tasseled weapon to the imposed changes of direction. The above characteristics amount to a second definition of a "well balanced" sword.

A balancing point distinctly forward the first third of the sword was still conserved in antique lighter swords of the late Qing dynasty, when the sword fall completely out of military use. This suggests that the tip-heavy and longer torque arm features were intentionally conserved, perhaps for martial reasons, since it can be easily corrected in light-bladed weapons just by providing them with more dense hilts.

Thus I believe that a short torque arm of 11-13 cm, achieved with a tassel, was used to make the sword slow reacting. This is a necessary condition imposed by the needs of exhibit, teach and learn the sword intricate and fluid movements with a weapon balanced to move slowly.

Once the rudiments of the sword art are thus acquired, the student may progresses to a more advanced practice, which amounts to learn as to control a sword balanced to be faster-reacting; this is achieved simply by removing the tassel. The later characteristics result from the increased torque arm; a bonus is the tip-heavy balance, which made the weapon more adequate for fighting purposes.

As I'll discuss below, this optimal compromise between two types of "well balanced" swords arises almost naturally in weapons that's follows closely the pattern of old-style swords.

The harmonically well-balanced sword

Center of Percussion

A third definition of a well-balanced sword originates in the legend of the "sword's center of percussion", perhaps of some value in reference to Western swordsmanship.

The center of percussion of swords and other cutting weapons is the point on the blade that, during a blow, transmits the totality of the cutting energy to the target.

A sword vibrates when delivers a blow. The vibration waves distribute in places of the sword that vibrate strongly, and others that do not. These last are called "nodes".

On a hypothetical "harmonically" well-balanced sword meant for fighting, a major node should be located at a blade point consistent with the striking principles of wushu swordsmanship. For example, the relatively sharp and solid middle third of the blade is favored in the frequent cutting strategy "Chop/cleave" [Pinyin: pi1]. If a node or center of percussion situated in that part of the blade is used to strike, it would prevent that part of the chopping energy disperses by generating blade vibrations.

Western sword smiths searched for sword designs that put the other major vibration node under the gripping point, in order to avoid the transmission of the blow to the gripping hand. There is some evidence indicating that Chinese sword smiths consistently took the opposite tack, that of try to damp the blade vibrations.

A first piece of evidence is that the earliest Chinese swords (Spring and Autumn period) present the hilt and blade cast together in a single piece, which effectively converted the whole sword in a single vibrating body.

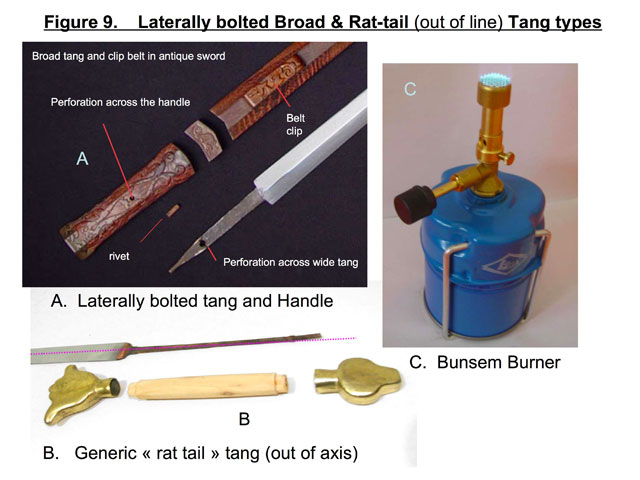

However that design had all but disappeared at the Qin and Han periods, and the short and solid tang, sometimes still tightly bound to the guard, was now articulated to the handle with a transversal rivet;

in this design, the top of the handle was presumably inserted and glued to the pommel Soon the tang become independent from the guard, handle, and pommel, which were strung together on the tang as beads, and secured both by a transversal rivet held in place by friction, or/and by riveting the tang's tail in the pommel.

In all these designs the common denominator is that the tang and the hilt pieces conserve some small degree of freedom of movement. The Chinese sword seems to evolve towards a tang tightly articulated to the different hilt pieces, a disposition that helps to disperse the tang vibrations. In this view, the tang is not a node in Chinese swords.

A second piece of evidence is the apparition of an advanced folded steel blade manufacture during the Han period. A folded steel blade can be viewed as a tightly packed wad of independent steel sheets, a disposition primarily destined to absorb shocks; a bonus of this array is the homogenization of the alloy composition, which was uneven in ancient steel.

A last piece of evidence seen in some types of Chinese and Middle East sabres are devices apparently intended to absorb the vibration of the weapon, as movable rings or steel beads somehow attached to the blade.

Most wushu adepts agree that a good wushu sword must respond with a perceptible vibrates to the "power discharges" characteristic of internal wushu schools (Pinyin: fa1 ji4n). I don't know if this affirmation comes from a genuine tradition, or if it is just some sort of wushu 'urban legend'. For one, we have seen that Chinese swords -and sabres- seem designed as to make these vibrations imperceptible to the user. Also, that dispersal of energy in sword vibrations contradicts the very definition of "power discharges", and the basic principle of energy conservation. On my very personal view, a well delivered " power discharge" should distributed its strength to all the body and weapons parts that have the potential to strike or parry, in a way stated by the form; vibrations are not the result searched for, rather an undesired by-product. The adepts that search to elicit sword vibrations during pretended power discharges almost always perform awkward gestures that impress as incorrect.

Whatever the definition of a well-delivered emissions of energy is accepted; the sword should allow the distinction. In this regard, the vibration frequency of a sword is influenced by the tang's elasticity. Since the tang, often of "rat tail" type

and the blade itself, are excessively thin in the vast majority of practice wushu swords, these necessarily vibrate at a frequency lower than that of a genuine fighting wushu sword. This feature may interest to purists that search for a weapon whose vibration modes during force emissions are more "genuine".

Some rare practice wushu weapons have these old-style tangs; this is the case of the "Ming/Shaolin" weapons shown in the Figure 3, and Tables 1 and 2; as expected these weapons present an agreeable and sustained low frequency vibration during the form performance. I have tried, with some success, to reproduce the same vibration feeling in weapons equipped with weaker tangs. The rigidity, and thus the vibration qualities of the weapon are much improved by filling the space existing between the handle and the handle, under the gripping point, with slow-setting epoxy glue poured by gravity from the pommel's end of the handle. This procedure was applied to two generic ("Han" and a "Yue") heavy swords with satisfactory results.

Being inalterable because determined by the weapon geometry and facture, the related "Center of percussion" and "harmonic balance" concept is of little interest in conditioning Chinese swords and sabres.

The position of the center(s) of percussion reached on a weapon well-balanced by the torque arm principle can be searched experimentally. If the weapon is held in the hand, when rapping the blade edge with a light stick, the sword should not evoke vibrations; incidentally, the natural frequencies of vibration of even heavy and rigid swords as the generic "Yue" and "Han" weapons mentioned in this Manual are too low to be audible; in both swords the a node for this vibration mode -or center of percussion- is located between the middle and last (point) third of the blade.

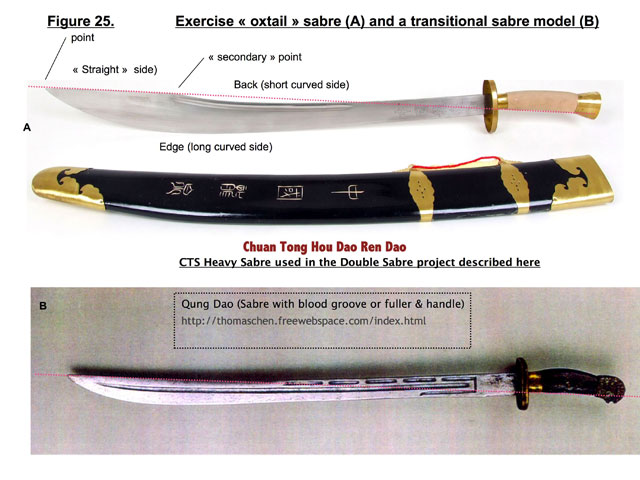

In the case of the rigid heavy double sabres, to be dealt with later in this Manual (see section "Conditioning of oxtail sabre kits for wushu training"), the high tapering in thickness of the blade produces at the broad point a diapason of sorts that can vibrates at high frequency (near the note f5), when the blade is struck. This high-pitched vibration mode is the hallmark of the modern machete, a chopping-slashing weapon that can be described as a straightened oxtail sabre; it is surprising to raise such a familiar and 'genuine' sound with an exercise Chinese weapon.

The apparent node -or center of percussion- for this vibration mode is nearly at 32,5 cm from the sabre point. Since this loud ringing is particularly distracting when training in double-sabre forms, is convenient to cross the sabres at this node when the form so it requires.

In the case of heavy sabres, the tangs are relatively more solid and realistic than usual in exercise weapons; the position of the experimentally found center of percussion should then be more representative of that of a true weapon.

Correcting the balance in old-style sword kits: How much weighs an old-style sword?

A length of 100 cm as average sword length, and a center of gravity located near the first third of the sword, is assumed in the following discussion. If we accept these assumptions, both the geometry of swords of these periods, and the nature of the materials then used in the construction automatically determine between narrow limits the weight and the balance characteristics of the completed weapon.

The Table 1 a, b, c) resumes the extent of my experience in the conditioning of heavy wushu kit swords (Figure 1). These weapons follow closely enough the general geometry of early swords, and have been equilibrated to achieve a center of gravity roughly located close to the first third of the sword, an optimal location for exercise.

Table 1b. Weight increase consecutive the conversion old style wushu sword kit in a "well-balanced" sword.

| Sword Type | Length | Weight "catalog" | Completed | Difference | Ballast share | |

| Sword | Tassel | |||||

| Heavy "Han" | 101cm | 1480 g | 1887 g | 407 (27.5%) | 192 g | 215 g |

| Heavy CTS "Yue" | 92cm | 950 g | 1248 g | 298 (32%) | 150 g | 153 g |

Table 1c. Effect of removing the tassel on shifting the center of gravity of a finished (well-balanced) wushu sword kit.

| Sword Type | Length | Weight complete with tassel | Center of gravity with tassel (%) length | Displacement of center of gravity forward, with the tassel excluded (cm) | Tassel weight |

| Light "Longquan" (1) | 104 cm | 620 g | 28.8 % (1/3.5) | 2.2 cm | 50 g |

| Light "Ming/Shaolin" (2) | 98 cm | 990 g | 28.7 % (1/3.5) | 1.1 cm | 40 g |

| Heavy "Han" | 101cm | 1887 g | 30.0 % (<1/3) | 4 cm | 215 g |

| Heavy CTS "Yue" | 92cm | 1248 g | 32.6% (<1/3) | 4 cm | 153 g |

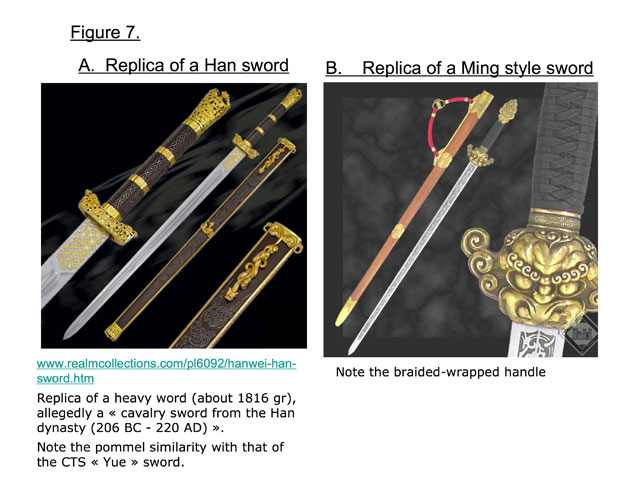

The final sword weights shown in Tables 1 (a, b, c) may surprise the wushu adepts used to light and flimsy weapons. However there is evidence that the weight of these reconstructions is not far from that of genuine weapons of the period. Reference 3 (article "On swords") indicate that the swords weights at the middle of the Ming dynasty (1368-1684) were respectively 1875 gr (3 jin, 12 liang [ancient weight units]) for the 100 cm (3 chi [ancient length units]) sword, 1438 gr for the 83 cm sword, and 1031 gr for the 67 cm sword. Also see Figure 7 for a 1816 gr replica Han sword (lien vers Figgure 7 agrandie et retour ici) Not surprisingly, the scaled military armor was still in use during this period (Figure 2A & C).

Were cavalry swords different than infantry swords ?

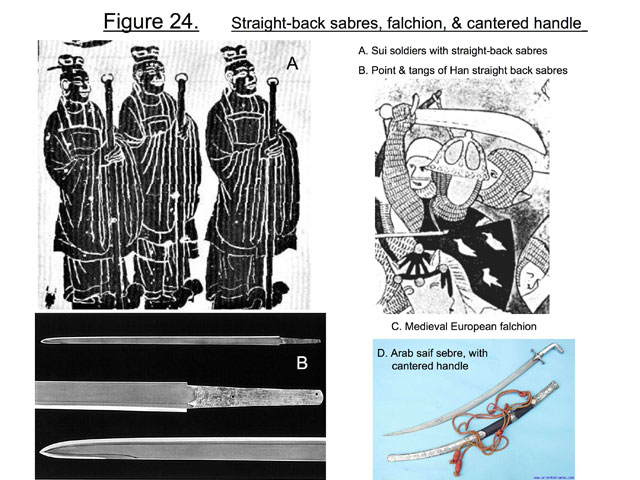

The evidence existing for such heavy swords raises some alarm among conservative wushu adepts, whom scramble to dismiss it. A commonly heard argument is that heavy Chinese weapons were intended for the cavalry soldier, and thus of no relevance to the forms of wushu practiced on foot. This may not be exactly true.

For the cavalry soldier in all cultures the practice of the sword and sabre proceeded to training on horse back only after a mastery of the weapon has been acquired on foot. Since a hand is needed to handle the mount, the cavalry weapons used on close quarters engagements must be handled with one hand. This approach to weapon training is desirable for the cavalry soldier, who always risks to be dismounted.

On the other hand, the sword and sabre were usually considered as secondary weapons for the horseman; their principal weapons were the bow and the spear. The larger Chinese two-handed short weapons belonging to the double-edged straight-sword and sabre family were not primarily intended to be used from horseback, but to provide the foot soldier with an anti-cavalry defensive and offensive potential.

Sword dimensions and the size of the swordsman

The evidence existing for such heavy swords also raises some questions and paradoxes.

Heavy swords were - and as I understand, they still are- the ones favored by the wushu styles that developed in Southern China, as T'ai chi; the average body size of the Southern Chinese was, and still is, lower than that of the Northern Chinese, whose emblematic wushu style -Shaolin- favor lighter swords.

In addition, the Chinese soldier of those earlier periods was presumably slighter in size and built than the average Chinese of today; this is also suggested by the Figure 24A.

A similar observation, well documented by the sizes of ancient armor suits, can be made for the contemporary Western soldiers. This also suggests that the sizes and weight of modern wushu weapons should be somehow up scaled to follow the recent population size increase, and allow a more realistic modern practice.

Most Chinese physicians I have interrogated agree that an average height of 150 cm is an adequate size estimation of the Chinese ethnic groups involved in the development of the internal wushu styles.

In conjunction, these arguments, and the internal wushu theory itself, are consistent with the notion that a 100 cm practice sword in the weight range of 1400 gr-1850 gr should be perfectly adequate for Western adepts 165 cm tall and a normal body built.

The very subsistence of a present days heavy wushu weapon manufacture suggest the survival of a tradition of internal wushu practice with the old style heavy weapons, which is in all comparable to the revival of historic musical instruments as the harpsichord and clavichord by Western performers of ancient music.

Choosing a wushu sword kit

If you practice a Northern sword style, the choice of a sword kit is easy; CTS and many other WEB and local suppliers have an ample choice of adequate kits (see the "Longshuan" and "Ming/Shaolin" sword descriptions in Tables 1a, 1b, and 2 for a description of such swords. Kits for such light weapons require little or no ballast, and the nominal catalog weights are more representative of the weight of the finished weapon.

The ideal practice weapon for internal sword wushu styles (Wudang, T'ai chi, etc.,) are heavy swords of the early pattern, which show thick and broad blades of diamond cross-section. Should you desire a still affordable kit for a very heavy sword of nearly 1850 gr, follow the link below toward "decorative swords". These "decorative" swords are equipped with forge steel blades, and are adequate for adaptation to wushu practice (I bought my own generic "Han" sword kit there).

Is dangerous to buy decorative swords for wushu practice, unless the dealer specifies that the compatibility exists, or if you are allowed to dismount the sword and check if the tang is solid, and forged on one piece with the blade. A blade just welded to the tang will yield a short-lived wushu weapon. On the other hand, if you choose as subject an adequate decorative sword you get a rewarding exercise weapon with top quality wooden parts, and carefully cast and finished metal fittings.

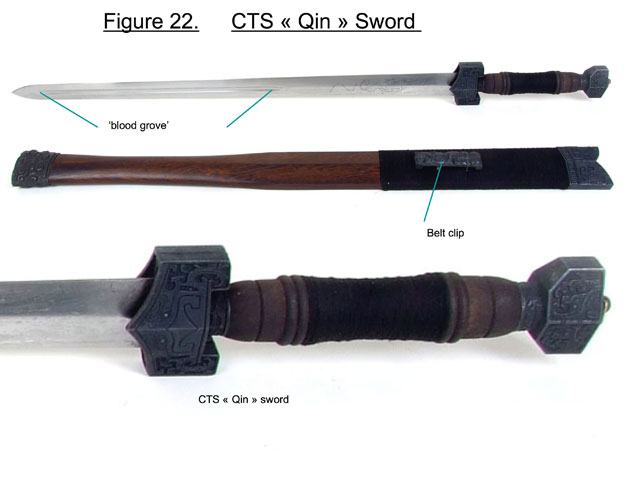

A group of excellent compromise 100 cm heavy swords less costly, and still challenging in weight, is represented by the CTS catalog swords "Yue" (1020 to 1300 gr), "Qin" (1090 to 1500 gr) & "Zhan Guo " (580 to 650 -700 gr) styles. The weight of the weapon as sold is indicated at the left of the arrow; at the right, my estimate of the weight of the completed weapon, tassel included. Is important to notice here that I have never actually conditioned sword kits responding exactly to these descriptions; these estimates are based in my previous experience, on the geometry of the sword considered, and on the conditioning of a 92 cm sword of the "Yue" pattern provided with a custom-made blade.

It will be difficult for me to refine my approximations without actual access to the weapon; the best I can do for the moment is to offer the interested reader my assistance by e-mail in this and other weapon projects.

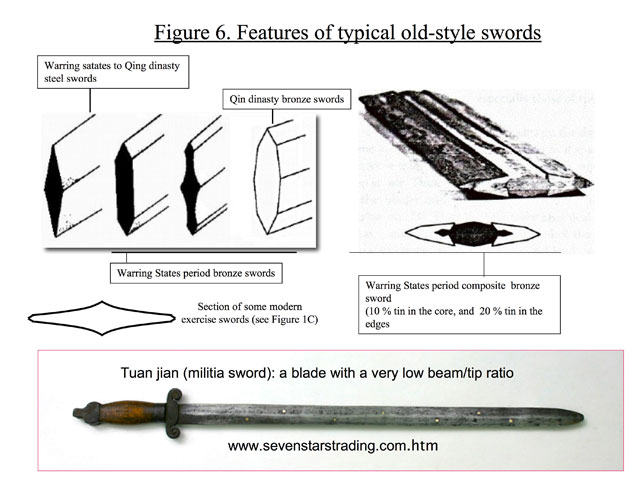

Most "old-style" blades are less tapered toward the tip (low 'root/tip' ratios) than the Northern blades (Table 2), which produce blades of a very characteristic shape, and a graceful "broad" effect. In this regard, compare in Table 2 the "root/tip ratios" for narrow and broad swords (Figure 6).

More importantly, the slight taper produces a sword with a blade heavier at the tip, and with more "angular momentum" (see below) than a sword of equal weight equipped with a blade of narrower and lighter tip. As we have already discussed, swords with a large angular momentum are more challenging in handling than swords with a high blade taper. Though rigid, a well mounted heavy blade still will react to the fluid weapon movements imposed by a slow performance of the sword form, responding with a strong and sustained low-frequency vibration clearly perceptible to the attentive practitioner.

Table 2. Tapering in beam and thickness in light and heavy swords

| Root (mm) | Ratio Root/Tip (1) | Total weight (gr) | |||

| Sword Blade Style | beam | thickness | beam | thickness | |

| Light "Longquan" | 33.9 | 5.55 | 1.53 | 3.08 | 570 |

| Light "Ming/Shaolin" | 31.8 | 4.55 | 1.37 | 2.08 | 990 |

| Heavy CTS "Yue" | 35.25 | 8.79 | 1.15 | 1.78 | 1248 |

| Heavy "Han" | 42.9 | 8.2 | 1.22 | 1.61 | 1887 |

1: measured at 60 cm from the root; all the blades in Table 2 presented an even taper in both thickness and beam (data not shown).

Lighter weapon kits

Handling an 1850 gr sword is certainly challenging for a beginner that, just learning the form, must hold every position for long periods. With a body weight of 80 kg, I learned my first sword form with the weapon of 990 gr that is described in Tables 1a, 1b, and 2.

Unless the adept is a natural choreographer (as most of high-level wushu masters are), it tends to develop bad handling habits using light swords longer than strictly necessary. I believe that as soon as possible the student should move to training with heavy weapons in order to obtain a good grasp of the internal wushu sword principles. A heavy sword won't displace correctly through the movements of a form unless is dragged or pushed by the movements of the practitioner's legs and hips. The arms and wrists become insufficient as unique sources of strength. Reciprocally, the arms and wrists are perfectly adequate to handle a light weapon by themselves, which often lead to a neglect of the movements of the lower part of the body.

Experimentally I found that the 990 gr sword was just good enough to discover the feeling just described; a sword of about 1,100 gr and 100 cm long gives distinctly this perception. Unfortunately, such swords are both rare and expensive, in the market of wushu exercise swords.

Conditioning a wushu sword kit

In the preceding sections I've described what considerations should be taken into account to transform a Chinese wushu sword kit into the sword most adequate to your practice. The sections that follow will show how to accomplish that goal.

The basic problem of equilibrating an old style sword:

In modern wushu weapon kits inspired in old-style heavy swords is that is essentially impossible to attain the optimal equilibrium point of the recommended for learning and practice in a naked weapon.

Hilt ballast

The main problem presented by these early styles is to obtain a well-balanced weapon consistent with a wushu training. In this rather early style of Chinese straight sword the blades are broad & thick, proportionally thicker at the sword tip than the modern version of the weapons. On the other hands the handles and pommels are comparatively slender, giving just enough space to introduce the ballast necessary to give a slightly tip-heavy sword.

Correcting the weight of the tang, pommel, and guard

In genuine fighting swords the tang (the blade part traversing the guard, handle and pommel) was usually thick, thus contributing to bring naturally the weapon equilibrium point to a more comfortable position, closer to the handle (Figure 9A & Figure 24B).

In addition, the pommel and guard were cast in a solid hard and dense metal or alloy, usually cooper, or bronze. Thus, once assembled, the weapon was, from its own design, close to the optimum point of equilibrium.

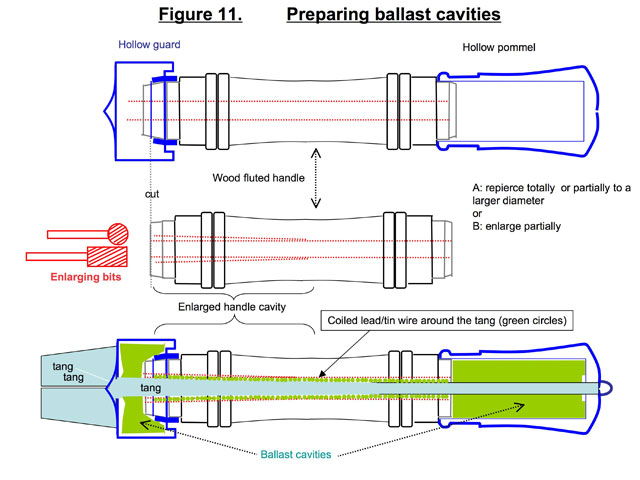

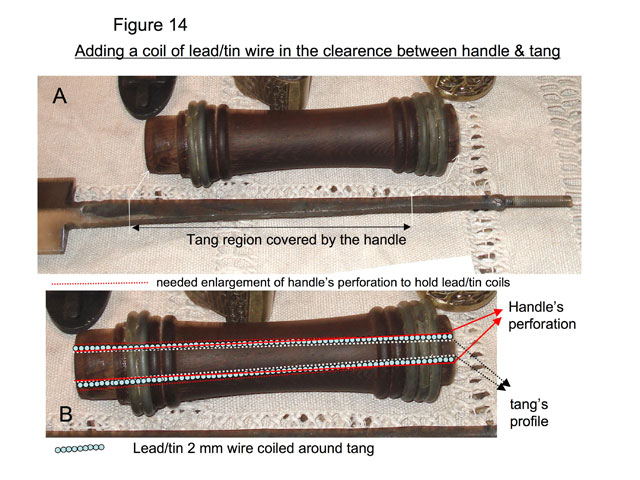

In the exercise version of the fighting weapon, the tang usually will be only as thick as needed to avoid the weapon to break during the solo practice of the form (Figure 9B); this design probably search to prevent the utilization of the weapon in actual fighting. The weight difference between a large tang and the slender tang of the exercise sword can be compensated adding ballast (bits of a highly dense metal carefully packed) in a clearance normally existing between the handle perforation and the tang itself. If needed, additional ballast can be added in a lodging produced by enlarging the handle's perforation at the top, next to the pommel; at this position the weakened handle do not interferes with a vigorous sword practice.

The guard of a sword kit usually is a hollow box cast in copper, bronze, brass, or an anodized metal alloy. In low prized sword kits the pommel, as the scabbard metal fittings, may be done in resistant plastic. These hollow cavities in the guard and pommel are to be filled with ballast, as to obtain a guard and pommel with the approximated weight expected from a piece of equal shape cast in a metal or alloy of intermediary density, as solid cooper or bronze.

Since some of the available space inside will remain unoccupied, even if dense ballast carefully shaped and packed is used, it will be difficult to achieve a pommel and guard weighing much more than if they were actually cast in bronze or copper. This is particularly true when the hollow pommel is made in plastic; plastic pommels have low density, and thick walls that reduce the space within. Such pommels must be filled with a very well packed and dense ballast to recover the weight expected of a solid copper pommel of equal shape.

If all these precautions are taken, you will get at the end a sword that will reproduce almost exactly the balance of the weapon which inspired the kit.

The tassel as ballast and learning aid

Probably the primary role of the sword tassel is the fine correction of the weapon balance. A long tassel, adjusted to the hilt is the traditional dress of the heavy swords associated to the T'ai chi styles. A tassel about of third of the weapon length is the one traditionally used in the Wudang sword forms. Northern swords forms are less fond of the tassel; but if they use one, it will be the short tassel.

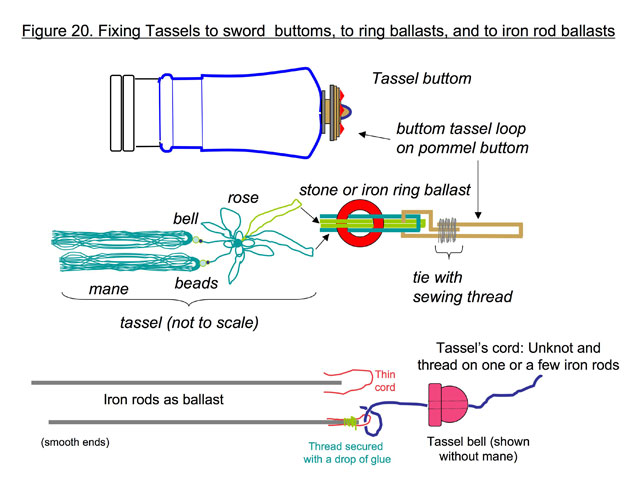

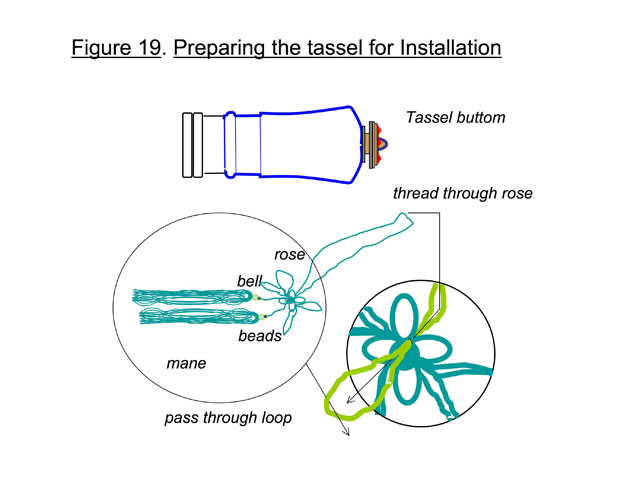

The long T'ai chi tassel (Figure 20) is made of a couple of 2-3 cm wooden "bells" covered each with a well nourished silky mane of 50 cm long, each inserted in a 50 cm length of silky cord. Tassels are light enough as to have a negligible influence on the sword's balance, though may secret lots of ballast.

Each bell hang from a silk string were a few beads of more or less dense materials (stone, porcelain, metal) are threaded and stacked on the top of the bell, thus giving part of the ballast. Both bell strings are knotted together by a complex decorative knot and often woven around a heavy stone ring, before being tied somehow to the pommel tip. A puzzling feature of ancient tassels is the existence of lengths of iron or steel wire hidden behind the silk mane, which have been interpreted as secondary weapons. In fact, most likely they represent just another additional resource to ballast the tassel. Upon a little practice with the tassel ballast, you will probably find that its optimal ballast distribution is of equal weights evenly spaced along the tassel.

The tassel has also the important educational role of teaching aid, imposing a fluidity and timing of the sword, hand and feet movements that prevent the tassel of tangling around the wrist, or just of being stepped on. The improvement a tassel imposes on the practice of the sword form largely outweighs the price of soiling and ruining a relatively cheap good quality long tassel. A good tassel should be the constant companion of a practice weapon. During the more ambitious practice with the weapon devoid of tassel, and thus tip heavy, this pedagogic role of the tassel is conserved by the mean of a lighter lanyard, simply made by a length of cord or a ribbon, tied to the pommel (Figure 2B); in some period representations at the Paris's Musée Guimet both strands of the lanyard are seen tied in a more or less complex rose, similar to that found in tassels.

In a future edition of these pages I'll indicate how to make your own tassels, if a particular project requires so; however these will prove to be much more expensive than also satisfactory mass-produced tassels. As a rule the later are much better than the tassels included with low-priced wushu swords, of poor strength and aspect, and inadequate for serious practice.

Conditioning a Sword of the CTS "Yue" pattern

The CTS "Yue", "Qin", and "Zhan Guo" sword patterns are not intended as reproductions of historical weapons.

These are to be evaluated as members of a class of generic weapons fundamentally intended for exercise, hitherto not available in Western countries that search to underline in an attractive and, over all, functional way some features of diverse Chinese swords from bronze and ancient steel era.

These periods are principally the Warring States (403 BC-221 BC, Qin (221 BC-206 BC), and Han (206 BC-220 AD) periods. The CTS "Yue" style sword kit represents a pleasant and well-designed weapon comparatively easy to condition, and thus I'll take it as a basic example.

Other reason of my choice is that I have recently conditioned a pair of CTS sword kits of this pattern "custom-made" to measure 92 cm (now a similar kit has become a standard item on the CTS catalog).

Its blade is broad, wide at the guard and slightly and uniformly tapered toward the tip; is also equally tapered in thickness. Note the similarities with a high-priced sword, supposedly a replica of a Han dynasty weapon (Figure 7). The blade uniform section (Figures 5 & 6) is roughly hexagonal, a characteristic frequent, but not exclusive, of Qin bronze swords. A feature of the CTS "Yue" and "Zhan Guo" large blade surfaces (Figure 6) is their slightly cylindrical section (Figures 1C & 23), which both reduces the blade weight and improves their aspect. I ignore whether this feature has any historical base.

Bronze and steel weapons co-existed for a long time, and probably features characteristics of bronze weapon were introduced in the first steel weapons before the experience of the military that used then, and the blacksmith that made them, conferred them their own personality. Indeed, in some high prized replica weapons the elegant and complex blade profile of the Warring States short bronze swords, present there for functional reasons, reappears for decorative purposes in the longer steel swords that supplanted them.

Ancient bronze and steel swords were difficult to tell apart in the battlefield. Bronze swords (at least Qin bronze swords) were protected from corrosion with an auto-deposed chromium layer. After the previous auto-deposit of a copper layer, this procedure was extended to the steel blades, still more vulnerable to corrosion than bronze blades. Often a third layer of nickel was also auto-deposed. The presence of traces of auto-electroplating is considered a hallmark of antique Chinese swords, but in fact the chromium cooper-chromium coat (I ignore if auto-deposed or electro-deposed) has persisted until today in an important group of heavy low-priced steel wushu weapons of semi-artisan manufacture.

The "Yue" sword

These swords are excellent didactic examples to introduce to the reader to all the current resources used in weapon balance and conditioning. The difficulties presented by these swords styles are not extraordinary, and make of these kits amusing projects. The resources that we'll learn here will remain valid to swords of styles less challenging to condition.

Disassembling the weapon.

Wipe off the oil excess and blunt the edges

Upon receiving your sword, wrap the handle in a cotton cloth and hold the weapon with it; often unfinished fittings project cutting edges, wooden shards, etc.

Wipe carefully from all the parts the abundant layer of jelly-like protective oil. Be careful, since the edges often are wickedly sharp. The kind of steel you get, also called 'martial steel' in the trade, is not intended to conserve an edge; the ones observed here are only secondary consequences of the artisan shaping of the blade to the desired hexagonal section.

This edge, and the roughness left by the milling should be removed. This can be done in one step, by carefully polishing the surfaces that meet at the edges with fine abrasive wet paper (starting with grit 600 or higher) wrapped around a block of hardwood or metal. Take care of grinding these surfaces at the proper angle, so the original section is conserved. Along the process insure that the edge is blunted, giving a minimum of strokes with the abrasive, in a sense perpendicular to the blade plane.

Protecting the blades from rust

Handle the blade with the same cloth you had removed the protective oil. As soon as a session of blade grinding is over, dry the blade and clean it with alcohol (CH3-CH2OH), to remove the remaining dampness and the corrosive body oils left with your fingerprints. In some countries the sale of pure ethanol is forbidden, unless denatured with traces of methanol (a mild toxic) to make it non-drinkable (then called 'burning alcohol'). Work in a ventilated space, and let dry outdoors the rags or absorbing paper containing alcohol before disposal (alcohol is inflammable, but highly biodegradable, thus it can also be disposed in a sink).

I'm told that the traditional Far East way to preserve steel sword blades and weapons was to anoint them with a layer of some essential oil or other; magnolia and clover oil are often mentioned among these.

Despite my affection for exercise wushu weapons, I draw the line on using such expensive substances to clean and preserve mine. For long time I anointed the blade with a very light coat of anti-rust domestic machine oil, without much success; the oil end by flowing off the sword and drips on the inside of the scabbard, were it is absorbed sometimes staining its exterior. The now unprotected blade rust easily.

Recently I've found that magnolia oil and clove oil can be advantageously substituted by the same mixture used in the section "Oil rubbing" to finish wood parts. This mixture, made of a part of lowly boiled linseed oil and a part of turpentine, resembles magnolia oil and clove oil in being a complex mixture of many reactive oils and a volatile solvent.

The turpentine-linseed oil mixture oxidizes at the air, thickening first to a jelly consistency, then to complete hardness, which makes a stable protective layer on steel.

The repeated use of the turpentine-linseed oil mixture on blades also removes iron-rust; even some seconds of rubbing a neglected blade with this mixture make it significantly cleaner and brighter. This mixture reacts with the scabbard wood, thus if any excess of it reach the wood, it is just fixed chemically there.

Dismount the sword

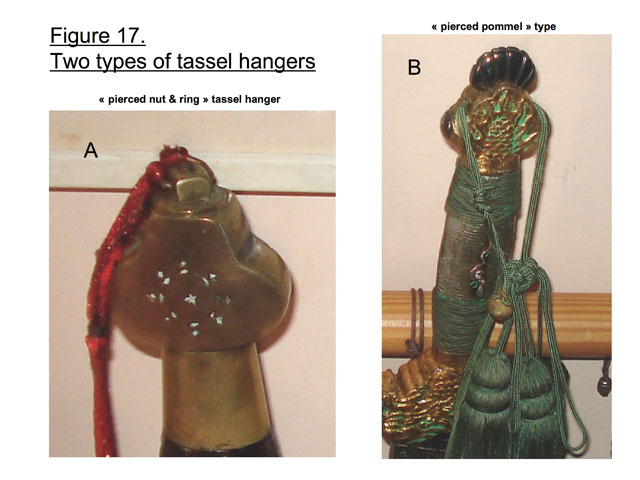

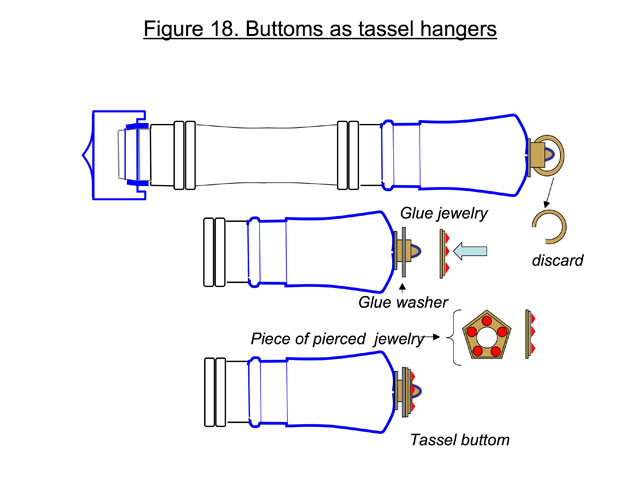

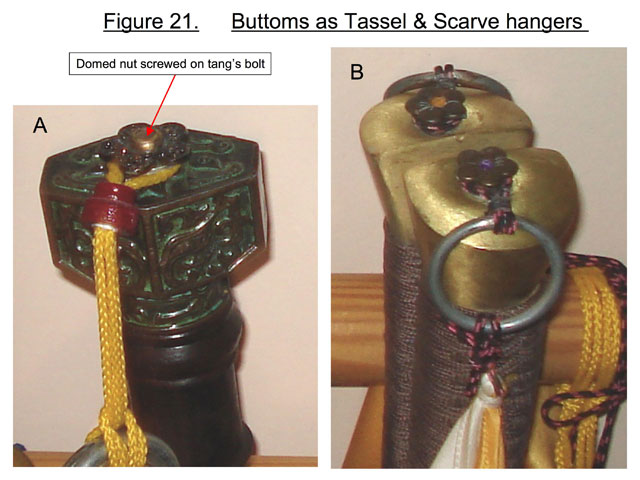

Now that the danger of handling the blade is reduced, dismount the sword. For this the ideal tool is a small narrow fixed-size wrench, of the type found in bicycle tool-kits, which can be eventually carried in your wushu bag. Use the wrench to unscrew the dome shaped brass nut (to be carefully conserved), which is screwed at the end of the tang (the blade part that traverses the pommel, wood handle, and guard). The brass nut usually has got two oppositely placed perforations were lodge the ends of a curved piece of cooper wire; this part is the intended point of attachment of the tassel. The tassel that usually comes with the CTS "Yue" swords is too small for any useful role, but comes equipped with a pretty artisan ring carved in some soft colored stone. Such rings are commonly found in tassels decorating swords of the Southern style. Keep carefully the stone ring, which will be part of the ballast integrated within a better tassel).

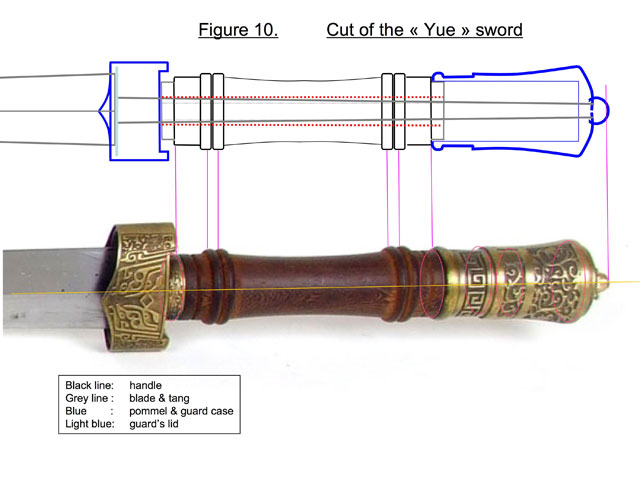

Retire the hollow fluted wooden handle, after making a sketch of its position relative to the guard and pommel; though superficially symmetric, the part of the handle hidden in the fittings might have different lengths and a diameter, giving some indications on the way the sword is held together.

It might puzzle you to discover that the attractive pommels of the CTS "Yue", and probably also those of the CTS "Qin" sword, are actually cast in high-impact plastic. Though imprecise, the moldings of the Yue pommel imitates so well a cast in brass or bronze that the fakery becomes evident only after disassembling the weapon. The scabbard fittings are also molded in excellent plastic.

Disassemble the guard

The hollow guard of the Yue style sword is made of two pieces cast on a resistant alloy, probably dark bronze. The oval shaped mouthpiece, includes a diamond-shaped lodging were the blade root is nested. The above mouthpiece fits accurately like a lid inside the guard piece. The opposite side of the guard piece is shaped as a neck where the handle is inserted. In high priced replicas often the sword pommel and the tip of the scabbard disassemble in similar way.

After disassembling the guard, wipe off the remaining protective oil, and clean it carefully, by immersing it in alcohol. Also remove from the sword's wooden parts all traces of oil you can reach.

Heat up to reach the minimal temperature that makes steel malleable (dark cherry red). Using a piece of cheap wood as anvil, straighten the tang with some moderate blows of a standard carpenter's hammer. Cool by immersing in hot water, or in mineral oil, in order to conserve the steel temper. Avoid heating the tang at a too high temperature (light red), since you risk making it brittle. Normally just a single round of heating and hammering suffices to get a tolerable tang alignment.

File off the protuberances and edges along the tang, removing the least possible material as to reduce its average diameter without actually weakening it. Take in consideration that the basic section of tangs is usually square. This is intended to even the tang diameter, and to facilitate wrapping a close-fitting ballast coil (below) to slide along around it. Clean the tang with steel wool, and cover it, excepting its filleted tip, with a coat of metal varnish.

Finish the blade adjustments.

Shape the sword's point and polish the edges to smoothness.

The outline of the blade you get may be summarily milled to the shape of the traditional Chinese leaf tip point (Figure 8), but otherwise incomplete. The finished point should continue the diamond shaped blade section into an eye-shaped section as it approaches to the tip; an unfinished tip, instead, will have a rectangular section at the same places (Diapositive8c).

First using a coarse oil-stone, then wet abrasive paper, shape a slightly blunt edge around the tip, milling its composing surfaces to make a blunt edge that will met at the same angle observed in the rest of the blade. This edge will continue around the tip the blade's edge; thus the tip also will have a hexagonal section all over.

During this process carefully avoid changing the point outline, which will be most likely already perfect . Set the sword hilt down & tip up between your legs. Pick two folded pieces of wet abrasive paper, one on each hand, held between the thumb and index, and round both edges at the same time. Let your fingers meet at the flat of the tip, reshaping it to an eye-shaped section. Avoid grinding off the tip edges. Turn the sword every few strokes, since in general both hands won't deliver the same pressure.

Do not proceed through big steps. Stop when the point is not yet fully shaped, polish with progressively finer grained wet abrasive paper, and then judge your work. The examination of the light reflecting in the shaped point is the best way to appreciate the symmetry of its grinding. It may take you sometime to learn how to take the point grind to perfection. At first, get a tolerable shaped point that is harmless to other practitioners and yourself. On each session of point grinding, search for remaining live edges, and kill them with fine grain wet paper.

Aligning the blade and the tang

Just watching from one end, or using as a ruler a straight table or door edge, verify if the tang is in line with the central ridge of the blade. Most of the time it will be the case (Figure 9B); four out of four of my CTS blades were not an exception to the rule.

If not in alignment, examine carefully the tang to see whether if it doesn't insert off center in the blade. A perfectly straight tang inside a handle's perforation that is off-center may produce an assembled weapon that looks misaligned. If this is the case, the handle might be re-centered by filing at the proper place with a round, and elongated wooden rasp. Always confirm your alignment by reassembling the sword.

If the tang is misaligned, find at which point is bent off line. Heat the tang bent in the flame of a portable Bunsen burner, or on a gas range (Figure 9).

Shape the blade root.

Once reassembled, the blade root may not fit snuggly within the groove in the guard's lid. This most likely is due to lack of alignment of the blade root surfaces that should be in contact with the aforementioned groove. Use a metal file, a coarse grindstone, or wet abrasive paper, mill off the faulty sword root surface to obtain a proper adjustment.

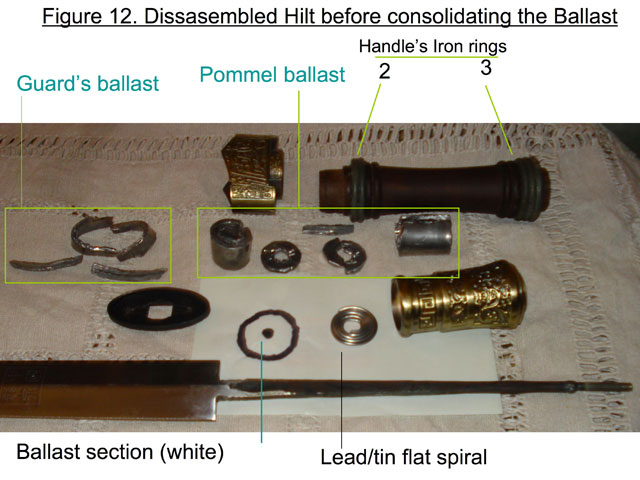

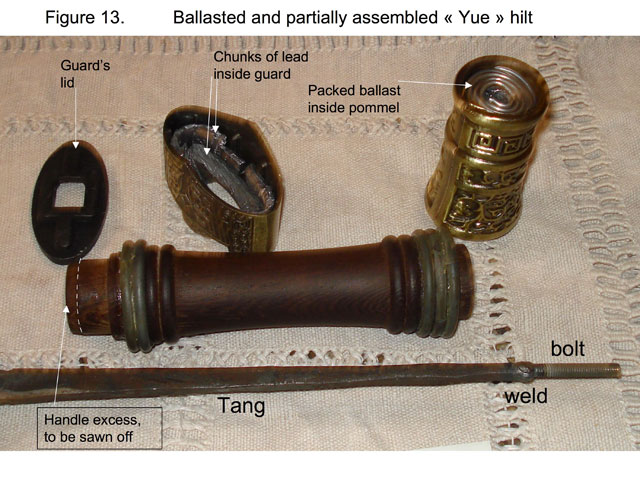

For obtaining an even root blade the safer way is to grind off the material and avoid the use of hacksaws and abrasive cutting wheel, unless you have an exceptionally well-equipped shop. Figures 10, 11, 12, 13, 14)

Prepare the weapon parts for ballast, & equilibrating the weapon.

Choice of ballasting material

The choice of the material used for ballast is conditioned by density of the material, that is the weight for volume unit. Iron and steel (density=7.874) are poor ballast materials given their small density; these rarely were used for making guards and pommels. Ancient guards and pommels were usually made in solid bronze or copper, respectively 12 %, and 13,8 % heavier, volume by volume, than iron or steel.

The hollow parts of the hilt of an exercise wushu sword kit (guard, pommel, and cavity between the handle and tang) must be filled with a very dense metal or alloy, to compensate for their low weight. Lead, 43.5 % heavier than iron or steel, volume by volume, is the best ballast choice; being soft and malleable, it can be easily cut in ballast pieces of the desired shape with woodworking tools, and shaped by hammering.

Lead sales to the public are forbidden in many countries, since if misused is toxic. If you have access to a good chunk of lead, do not hesitate to use it; lead weighs made with protective gloves, covered by a coat of metal varnish or epoxy glue, and in addition protected by the hilt's fittings themselves, are inoffensive to the sword user. If you don't have access to lead, the second best option is the lead/tin soldier adjuvant used in welding.

The cheapest kind of come in bars of 1 cm thickness and contains 60 % lead. The remaining 40 % is accounted by tin. This alloy though less dense than lead (density = 9.786; 13, 4 % less heavy than lead, though 24.3 % heavier than iron or steel, volume by volume), is less toxic than pure lead, and. A little harder and less malleable, still can be shaped in the same way than lead.

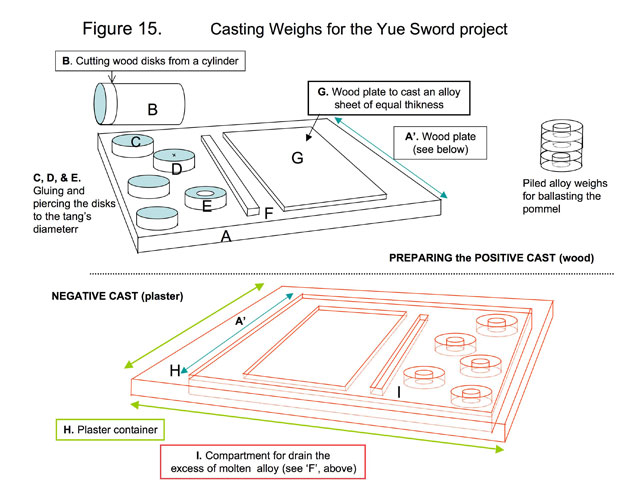

If you have some previous experience casting bullets or fishing weights, you may decide to cast your own ballast at the desired final shape. The alloy melts at lower temperature than lead, which reduces the danger inherent to its utilization. In this project the more useful shapes are pierced metal disks, or sheets of metal from which the ballast pieces are cut.

The Figure 15 takes you through the steps needed to make a plaster ("plaster of Paris") mould for casting weighs.

Only use tin/lead soldiering adjuvant in bars, without incorporated cleaner. The wire form, usually with an incorporated cleaner, should be avoided be used for casting, since the cleaner vaporization at the fusion temperature may produce potentially dangerous molten metal projections. Use thick clothes, shoes and goggles. Melt the alloy in a small solid iron or steel ladle. Never overheat the molten metal. Everything is just right when some non-molten fragments still remain in the molten metal. If you do not have experience on this, you may try a small scale test run to get the feeling of the material, and loose your natural fear to it.

The main advantage of the lead/tin alloy in wire form is that can be used directly, by wrapping it around the parts one wants to ballast. In order to obtain the desired sword balance, this kind of ballast must be carefully packed, as to achieve the best possible utilization of the limited space available within the hilt's components. In extreme cases a project might need lead/tin alloy in a more compact form than wire. Though expensive, fishing weighs are a good alternative source for more compact ballast.

Provided that this precaution is taken, and given its density higher than that of bronze or copper, lead/tin wire ballast can be utilized to reproduce the weight of a genuine old-style sword hilt. Hence I'll stress in this Manual the utilization of the wire form of tin-lead soldier adjuvant, which can be obtained everywhere, and is safe and easier to use; this should be your ballast of choice if this is the first time you attempt to condition a wushu weapon.

Cutting the handle to length.

Examine how the wooden handle is articulated to the guard. In the CTS "Yue" sword pattern the handle just repose in the guard's neck, and the solidity of the sword arrangement is determined only by the close fit of the tang to the inside of the handle, and the accurate lodging of the blade root into the guard's lid; thus the tapered part of the handle -its last 5 mm- can be sawn off, using a fine-toothed ribbed saw, in order to liberate room for more ballast (Figure: disassembled "Yue" sword hilt).

This wasn't done in the handle shown in the Figures 11, 12, & 13, since lead, a more dense ballast, was used in this project; also note that for the same reason the ballast is not as tightly packed as it could be. In some designs the handle prolongs through the guard to rest in a secondary neck cast inside, and as part, of the lid; in these cases, the original disposition should be respected.

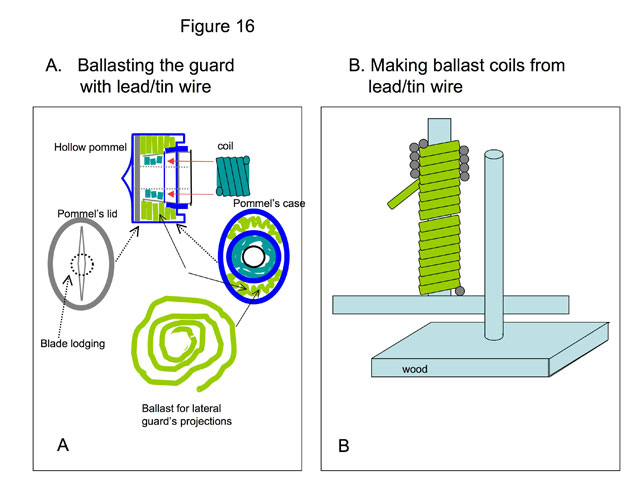

Filling with ballast the guard and pommel

Secure stably on a vice (wrapped in a cloth to avoid scratches and breaking the fragile bronze case), or on a chunk of modeling putty (Figure 16A). Wrap around itself a piece of lead/tin wire ballast, and compact by hammering on a piece of thick hard wood or metal. Pack to a close fit within the guard's case lateral projections. Avoid to fill the cylindrical part of the cavity determined by the end of the guard's neck, handle and lid, which will be filled later by a wire coils (Figure 16B); otherwise try to pack the ballast without leaving empty space.

A similar strategy should be extended to ballast the CTS "Qin" sword kit pommel, whose outline is similar to that of the "Yue"'s guard.

The Figures 12 & 13 show an alternative way to add the ballast to the open guard piece; in this case the ballast was cut from lead sheets, and is loosely unpacked; you must do a better job if you use lead/tin wire ballast. When you use this approach, check that the lid still can be put in place before and after consolidating the ballast.

Once satisfied, thoroughly mix a small quantity of quick setting epoxy filling paste, and distribute it over the packed ballast. Press as to force the paste to infiltrate among the ballast bits, and against the cavity walls. The purpose of this is to secure the ballast, to avoid it to rattle when using the weapon. Remove the epoxy putty stains from the guard, and from your fingers with a Q-tip, cloth or absorbing paper just dampened in alcohol. Do not use an excess of alcohol, which if mixed to the epoxy will prevent a good hardening. Once the putty is hardened, proceed similarly with the other guard lateral projection.

The cylindrical Yue pommel, and the cylindrical cavity left under the handle's insertion on the guard's neck, can be filled with ballast weighs made by piling up disk-shaped spirals made of coiled lead/tin wire; one of these is shown in the Figures 12 &13. Later (section " Making lead/tin ballast coils") I'll show a different way of make weighs that potentially allows a more close packing of the lead/tin wire. Construct these weighs.

At this stage is assumed that the sword's guard lateral projections are full to capacity with consolidated ballast. You also dispose of consolidated weighs that fit tightly to the cylindrical cavities in the guard a pommel

Consolidating the guard to the blade

At this stage you should have a guard whose lateral projections are with filled lead/tin wire stably set in place with epoxy putty, and a coil of lead/tin wire that fits in the cavity. The size of the coil should allow for the insertion of the guard's lid, were the blade root rests, and for the projection of the handle inside the whole guard's neck. If these conditions are fulfilled, set the coil in place with a small quantity of quick setting epoxy glue, using shims of lead/tin wire eventually hammered flat to center it on the weapon axis. Clean the eventual glue excess.

Once the glue is set, add -without gluing- additional shims as to fill most of the space still left inside the guard. Mix a small quantity of quick setting epoxy glue spread around the edges, glue the lid in place, wait for the glue to set, and clean the eventual glue excess.

Reassemble the sword in order to examine if the handle still enters correctly in the guard's neck, and if the weapon is still aligned.

Grind in the blade root top to expose a fresh metal surface. Verify once more that its adjustment of the blade lid is nearly perfect. Glue it to the lid, now with the more resistant slow-setting epoxy glue. Use a small quantity of glue, to avoid that it excess leaks through and reach handle, sticking it to the guard's neck. Usually I take the precaution of interposing some thin aluminum foil between the handle end and guards neck. Reassemble the weapon, securing it tip up. Remove glue stains from the blade, and let the epoxy dry at least overnight,

Disassemble the weapon; the handle might be partially glued to the guard by a join easy to tear off, thanks to the fragility of the interposed aluminum sheet.

The guard should be now glued to the blade. Sometimes the cooper and bronze guards of historical weapons were directly cast around the blade; this is the method we will try to reproduce to obtain a dense handle.

Insert as more lead/tin shims as possible in the clearance eventually left between the cylindrical ballast coil, and the tang and guard lateral ballast. Set the sword tip down, and mix thoroughly an abundant quantity of slow setting epoxy glue on some thick paper (for example a calling card), and use the same paper, rolled as a funnel, to pour the glue on the guard's neck. Left rest for 15-30 minutes to allow the glue to flow by gravity towers the lid.

Most likely all the glue added would infiltrate between the loose ballast bits, leaving intact the space inside the guard's neck were the handle lodge. You might use the tip of a bamboo skewer to help the glue infiltration in the ballast. Remove carefully the glue stains from the inside of the guard's neck. Verify form time to time that the glue does not leak from the joint between the blade root and guard's lid. In the unlikely case that this happens, clean the glue, and seal with chewing gum. Remove the chewing gun not before after 5 hours of setting and clean the possible stains of semi-solid glue; let the glue set for a total of 12-24 hours.

How much more weight for balancing your weapon?

Reassemble the weapon, including the weighs you just build.

Ballasting the tassel

Good quality tassels ordered as accessory are heavier than the rickety kind usually included with the weapon kit, since carry more cord on the mane. Weave on the tassel a stone ring, or one or more blackened iron rings, as indicated in the Figure 20. A simple Chinese stone ring is the traditional decoration of tassels affected to heavy swords designs. Convenient -and quite expensive- stone rings are ubiquitous in the Chinese quarter decoration shops (hopefully your city is blessed with one), or in Western New Age shops.